August 12, 2020

By Marianne Engelman Lado & Jameson Christopher Davis JD’20/MELP’19

Welcome to the Environmental Justice Clinic’s new blog series, in which student teams interview clients and partners from across the country. Over the next six weeks, we’ll hear their perspectives on the connections between environmental justice, the struggle for racial justice, and the Movement for Black Lives.

In 2017, Vermont Law School (VLS) attracted students from across the country to its strong environmental law program but offered only one class on environmental justice (EJ). That fall, students Sherri White-Williamson, Ryan Mitchell, Margaret Galka, Jameson C. Davis, Arielle King, Kyron Williams, and Jessica Debski took action, forming the Environmental Justice Law Society (EJLS). In furtherance of its mission, “Fighting for environmental justice through education, advocacy, and knowledge of the law,” EJLS has been a force in the fight against environmental injustice both within the Upper Valley of Vermont and New Hampshire and nationally.

Today, EJLS continues to evolve, highlighting the burdens faced by EJ communities while continuing to dedicate resources to educate local municipalities, governmental entities, and students on the history and impact of EJ. In response to this significant student interest in environmental justice, VLS launched the Environmental Justice (EJ) Clinic in fall 2019. The new clinic serves communities across the country that are fighting environmental racism – particularly racial inequalities in the location of polluting sources such as refineries, landfills, incinerators, industrial animal facilities, and diesel emitting highways and the failure of local, state, and federal governments to ensure that all residents of the country are equally protected against environmental harms.

Chokeholds and Environmental Injustice

The EJ Clinic represents and partners with residents of environmentally overburdened communities who for years have been saying, “I can’t breathe” when faced with choking air pollution. For Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) communities, chokeholds that harm and even cause death are not always physical and do not always happen at the hands of law enforcement. Chokeholds occur when toxic waste sites, landfills, and power plants are concentrated in already environmentally overburdened BIPOC communities, and children grow up experiencing the health effects of living in proximity to so many sources of pollution. Chokeholds occur when, in pursuit of a basic education, BIPOC students are forced to sit in classrooms filled with mold, asbestos, and many other toxic and harmful chemicals that shorten their life spans and brain development. Chokeholds occur when wastewater discharge and air permits required by law are not properly enforced, allowing communities to be impacted by toxic pollution on a consistent basis, with no end in sight. Chokeholds occur when low-income and unincorporated BIPOC communities lack proper sewage and sanitation, creating the conditions for the spread of disease.

We now learn from emerging research that COVID is more likely to spread in areas with greater air pollution and, also, that people are more likely to become ill and die from COVID in communities with exposure to pollution. Reduced capacity to fight off infection due to pre-existing health conditions such as asthma, resulting from long-term exposure to air pollution, puts BIPOC communities at higher risk of death from the virus. The pandemic has made clear to many what residents have long known: living near greater concentrations of air pollution contributes to racial disparities in illness and death.

Death by a thousand cuts – or by thousands of moments breathing in dirty air or drinking contaminated water – is still death, and concentrating facilities in BIPOC communities is no less a reflection of whose lives society values. For decades, BIPOC communities have organized through the Environmental Justice Movement to say enough is enough. Why should BIPOC children grow up with higher asthma rates and shorter life spans? Why does society fail to listen when BIPOC communities say, in the environmental context, we can’t breathe, we don’t have access to clean water, or we don’t want our children playing in contaminated soil?

On the Frontlines of a Movement

These past months, protests have sparked across the country in response to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, Elijah McClain, and countless others. These protests have become a catalyst, sparking authentic conversations, and exposing the ways false ideas of white superiority within our institutions and structures intersect with the environmental burdens placed on low-income and BIPOC communities. Environmental organizations are talking about the ways their own internal processes, procedures, and history have failed to combat environmental racism. Civil rights leaders of the ’50s and ’60s knew then what many “Big Green” organizations are grasping today: There is no climate justice without environmental, social, and racial justice. One cannot conserve the lands without also protecting people. EJLS and the EJ Clinic are dedicated to using our platforms, resources, and legal expertise to amplify the voices and message of those on the front lines and most vulnerable who have been developing a community- and justice-based platform for change.

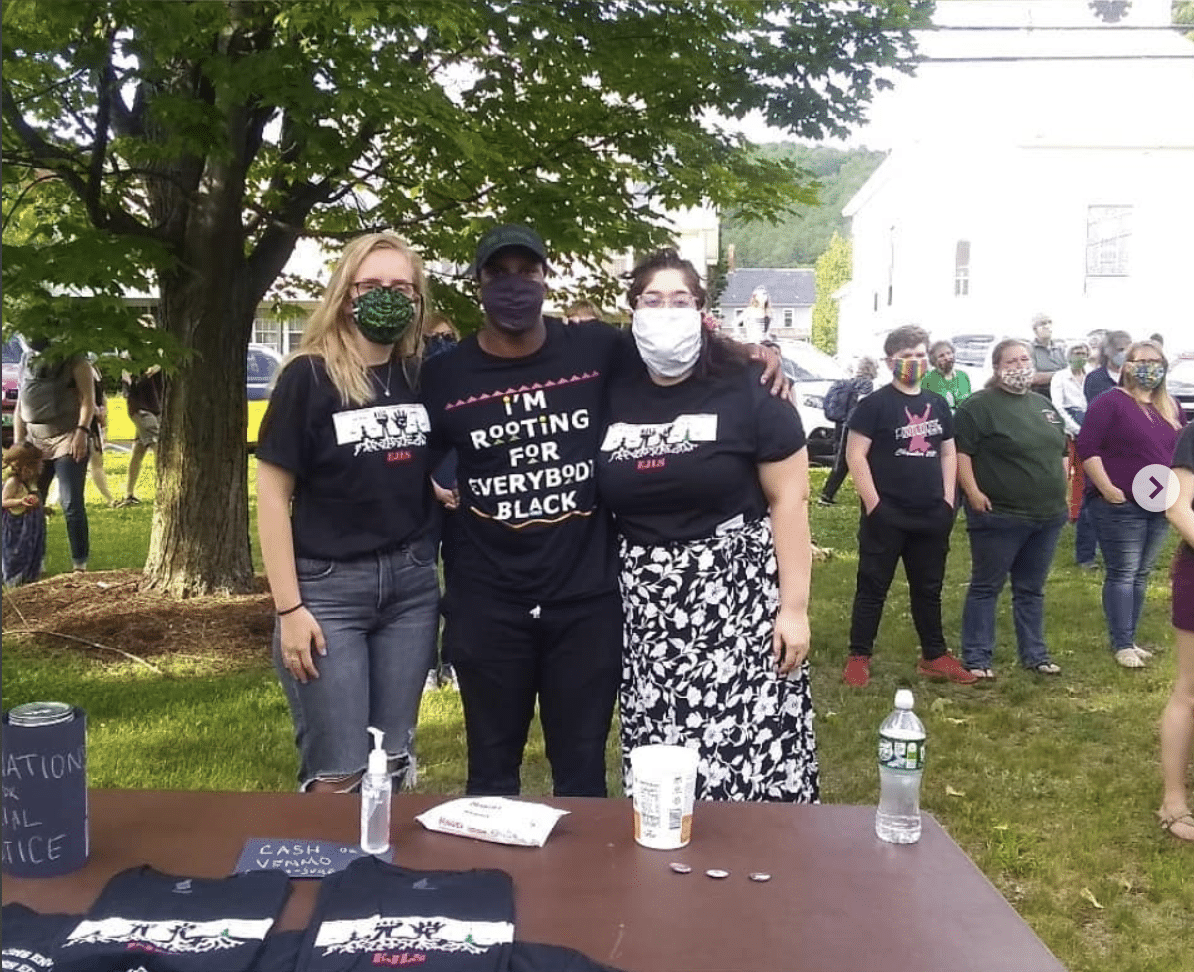

selling t-shirts at a Black Lives Matter rally.

Rather than addressing racial disparities, the Trump Administration continues to lower environmental standards and undermine meaningful community participation in decisions that can have life-or-death consequences. This spring, the EJ Clinic filed comments with WE ACT for Environmental Justice on behalf of 29 organizations and seven environmental justice activists and scholars on the Administration’s efforts to turn the clock back on two key protections provided by the National Environmental Policy Act. The new regulations, recently finalized by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), limit public participation and restrict consideration of cumulative impacts in decision-making connected to major federal projects. We strive for a positive, more just vision of the health and welfare of the country and are committed to continuing to support community groups as they fight rollbacks in protections.

We know that change is coming, and, at this moment, when our clients and partners have taken to the streets to demand justice, EJLS and the EJ Clinic are asking what more we can do. In June, EJLS continued its dedication to advocacy, donating funds to both the NAACP-Rutland (Vermont) and The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond (National/International). In July, the EJ Clinic joined with partners on a Call to Action, affirming that Black Lives Matter and calling for an end to the disproportionately high rates of illness and death experienced by people of color as a result of environmental racism. The first item on an agenda for change is equal protection – among other things, robust civil rights enforcement to address inequalities in housing and environmental exposures. In August, EJLS partnered with local cinematographer Anthony Marques and prominent EJ/Climate justice leaders Mustafa Santiago Ali, Raya Salter, and Nadia Seeteram to develop EJLS’s first documentary, Trace the Roots. Trace the Roots is a video project centered around the important discussion of why or why not traditional white-led environmental organizations should align themselves with the current social and racial movement.

Amplifying Client Voices

As we consider where to go from here and continue to use our resources to support those on the front lines of the fight for equality and equity, the EJ Clinic and EJLS are guided by the Environmental Justice Principles. These principles were developed by community groups who came together in commonality and protest against environmental racism to form the Environmental Justice Movement in 1991. Of particular significance for our work, they include a demand that policy be based on mutual respect and an affirmation of the fundamental right to self-determination.

Support for the right to self-determination begins with hearing the voices of environmental justice communities. Toward this end, we are excited to announce the launch of EJ Clinic Conversations, a weekly blog series written by EJ Clinic students after sitting down with clients and partners from across the country and hearing their perspectives on the connections between environmental justice, the struggle for racial justice, and the Movement for Black Lives. These include conversations with José Bravo, the executive director of Just Transition Alliance, Naeema Muhammad, Organizing Co-Director of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network, and others. The first installment will appear on the VLS blog next week.